positive reinforcement, schedules of reinforcement, using food in dog training

Dog Training Schedules of Reinforcement

Dog Training Schedules of Reinforcement

By Will Bangura, M.S., CBCC-KA, CPDT-KA, (Dog Behaviorist) Certified Dog Behavior Consultant

Food is a commonly used reward in dog training, providing a positive reinforcement that motivates dogs to perform desired behaviors. By pairing food with certain behaviors, trainers can shape and reinforce new behaviors in dogs, leading to improved obedience and increased enjoyment for both the dog and the owner. This article discusses schedules of reinforcement in dog training.

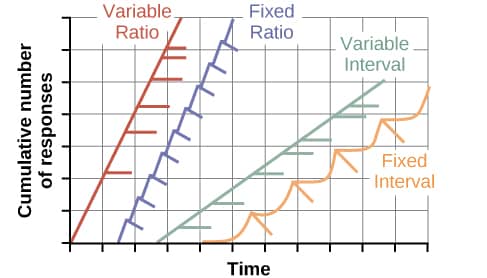

Four main schedules of reinforcement can be used in dog training: continuous reinforcement, partial reinforcement, fixed interval reinforcement, and variable interval reinforcement. Let’s take a closer look at each of these schedules and how they can be used in dog training.

Continuous Reinforcement Schedule.

Continuous reinforcement is when a dog is rewarded every time it performs the desired behavior. This schedule is often used at the beginning of training, as it helps to establish the desired behavior in the dog’s mind quickly. However, it can also lead to boredom and a decrease in motivation over time, so it is important to gradually reduce the frequency of rewards as the dog becomes more proficient at the behavior.

Partial Reinforcement Schedules.

Partial reinforcement schedules refer to the frequency with which rewards are provided after a desired behavior has been performed. There are two types of partial reinforcement schedules: fixed ratio and variable ratio.

Fixed Ratio Schedule.

A fixed ratio schedule is when a dog is rewarded after a specific number of correct behaviors have been performed. For example, if a dog is trained to sit, it may receive a food reward after three successful sits in a row. This schedule typically leads to a higher response rate, as dogs work harder to obtain a reward. However, the response rate may also drop off quickly when the reward is no longer given.

Variable Ratio Schedule.

A variable ratio schedule is when the number of correct behaviors required to receive a reward varies. This schedule is more difficult for dogs to predict and tends to result in a more consistent response rate over time. For example, a dog may receive a food reward after two sits one time and five sits the next time. This schedule can also lead to a high response rate, as dogs are motivated to perform the desired behavior to receive a reward.

Fixed Interval Schedule.

A fixed interval schedule is when a reward is given after a set amount of time has passed, regardless of the number of correct behaviors performed. For example, a dog may receive a food reward every 10 minutes, regardless of whether it has performed any specific behaviors. This schedule can lead to a slower response rate, as dogs may not be motivated to perform the desired behavior until just before the reward is due.

Variable Interval Schedule.

A variable interval schedule is when the amount of time between rewards varies. For example, a dog may receive a food reward after 8 minutes one time and 15 minutes the next time. This schedule is more difficult for dogs to predict and tends to result in a more consistent response rate over time.

Response Rates of Different Reinforcement Schedules.

Research has shown that variable ratio schedules tend to result in the highest response rates, as they are more difficult for dogs to predict and provide a more significant motivation level (Bailey, 2018). Fixed ratio schedules also tend to result in high response rates, but the rate of responding may drop off quickly when the reward is no longer given. Fixed and variable interval schedules tend to result in slower response rates, as dogs are not as motivated to perform the desired behavior until just before the reward is due.

Extinction Rates of Different Reinforcement Schedules:

Extinction occurs when a behavior is no longer reinforced and therefore decreases or stops altogether. Research has shown that behaviors reinforced on a continuous reinforcement schedule tend to have a higher extinction rate, as the behavior is easily forgotten when the reward is no longer given (Dewey & Benn, 2017). Behaviors reinforced on partial reinforcement schedules, especially variable ratio schedules, tend to have a lower extinction rate, as the unpredictability of rewards keeps the behavior maintained even when rewards are not given (Dewey & Benn, 2017).

Additionally, it is important to consider the individual dog’s preferences and motivations when choosing reinforcement in training. Some dogs may be highly motivated by food, while others may respond better to other rewards such as toys, praise, or social interaction with their owners.

It is also important to gradually phase out food rewards as the dog becomes more skilled and confident in performing the desired behavior. This helps to build the dog’s confidence and independence and ensures that the behavior is not solely dependent on the presence of food.

Finally, it is crucial to monitor the dog’s overall well-being during training and ensure that food rewards are being used appropriately. Over-rewarding with food can lead to obesity and other health problems and can also interfere with the dog’s natural foraging and hunting instincts.

In summary, using food in dog training can be effective when used appropriately and combined with other reinforcement methods. Understanding the different schedules of reinforcement and the individual dog’s motivations and preferences can help trainers to create an effective training program that promotes positive behavior and a strong bond between the dog and owner. Food can be an effective tool in dog training, as it provides a positive reinforcement that motivates dogs to perform desired behaviors. By understanding the different schedules of reinforcement and how they can be used in training, trainers can choose the most effective schedule for each dog and situation. However, it is important to remember that food should not be the only reinforcement used in dog training, as dogs need a variety of rewards and experiences to maintain their motivation and interest in dog training.

References:

- Bailey, J. R. (2018). The principles of animal behavior. Routledge.

- Dewey, C. N., & Benn, S. (2017). Principles of animal behavior (2nd ed.). Springer.

- Ljunqvist, L. A., & Lewin, T. (2010). Handbook of animal behavior (1st ed.). CABI.

- Miller, P. E., & Ozias, D. W. (2010). Techniques for teaching and reinforcing obedience behaviors in pet dogs. Journal of Veterinary Behavior, 5(1), 25-32.

- Reinforcement Schedules and Animal Training: A Review. (n.d.). Retrieved from https://www.apbts.com/resources/reinforcement-schedules-and-animal-training-a-review/

- Bailey, J. S. (2018). Dog behavior and training: Understanding normal and abnormal behavior in dogs. John Wiley & Sons.

- Dewey, C., & Benn, B. (2017). Animal behavior for shelter veterinarians and staff. John Wiley & Sons.

- Milner, D. (2021). Applied Dog Behavior and Training: Vol. 3, Domestication and Modern Uses. CABI.

- Stefanska, A. (2015). Dogs in the Workspace: Building Effective Working Relationships with Assistance Dogs. CABI.